Sunday 8th December 2019

For Words Weekend

4pm – 5pm

Northern Rock Foundation Hall

Sage Gateshead

SLIDE 1: SEA RESCUE CARMEN MARCUS

I’m Carmen Marcus, author of How Saints Die and I’m going to talk this windy afternoon about what it means to really ‘go under’.

I’m going to be your guide under the sea and its stories. I’m terrified of water. But that makes me the best guide. It takes courage to look into the scary places.

Getting to the place where the light can’t reach will feel like drowning and only then we do we discover the practical magic that is in the deep unconscious – Helene Cixous describes this place perfectly in the laugh of the Medusa as –

‘that other limitless country, the place where the repressed manage to survive’ Helene Cixous

Only there do we understand how the sea can rescue us.

SLIDE 2: CARMEN AND DAD

Sea Lore, Paracosms and Magical Realism

Meet my dad and me, Daisy Ellen the boat and my uncle Rodney.

My dad was a fisherman, he fished the seasons, he never learned to swim because if the sea decided to take you then you didn’t fight. That was the bargain for taking your ‘brothers and sisters from the sea’ , Ernest Hemingway got this.

My dad’s life was the sea, he was in the navy and supported lifeboat rescues and because of what he’d seen, he was very very very frightened of the sea. But still didn’t learn to swim?

Most parents take their kids to the beach during the summer holidays for a bit of a paddle for fun.

Not my dad. He took my sister and me down to the beach at 6.30 one morning before the best part of the day was over – usually about a quarter past seven.

He took us right up to the water’s edge, he held our hands and said ‘see this’ and he padded the wet sand with his giant foot ‘the law of man and god stops here and the law of the sea begins.’ Then he sucked in his breath and told us never to go in over our knees.

So I grew up very aware that there is an edge to the human world, that roads end abruptly and give way to dunes and a vast blue fear.

To counter this fear, we had stories.

This is my family story…

My great great grandfather, James, was out on the boat one day and there was a huge catch, the net was bulging but as they hauled it in, James saw something like a porpoise or a seal caught in the nets. It had huge expressive eyes that looked right at him. He knew then it was a sea god. He did not hesitate. He cut the nets and freed the god. Just before it dived down deep within the waves it promised that all of my family would be protected at sea.

And we haven’t lost anyone to the sea despite two world wars in the navy, generations of fishing folk and lifeboat crew.

So when I first heard the Selkie tale, a story about a seal woman, whose skin is stolen by a fisherman, about the capture and domestication of a wild creature from the sea, I knew that this tale was dangerous because it broke the rule – you always cut the wild thing free!

And because this is a danger story, there is so much to be learned from it about theft, capture, going under and surviving.

Firstly, I’ll tell you the raw story.

Then I’ll show you how working with the bones of this myth helped me find a way to tell the truth about my mother’s mental breakdown in How Saints Die without shame. And then we’ll look into the dark depths of this tale – as a warning tale – and what it reveals about patterns of coercive control and how to survive it.

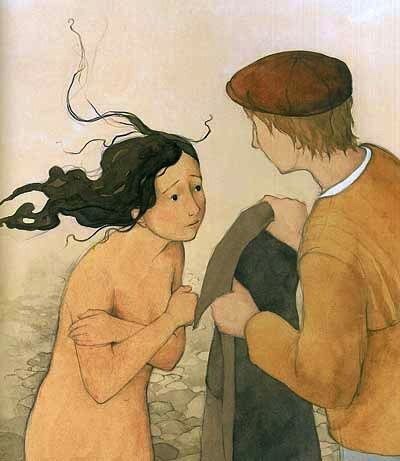

SLIDE 3: SELKIE

The Selkie Story – I’ve adapted and played with this story from the Selkie Story from For Women Who Run With Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estes.

A fisherman gathered his baited lines and rowed out into the dark cold morning. He was too tired to see the stars in the water. Not no-sleep tired. The other kind that makes you slide into the grooves of routine without thinking or feeling. The fisherman mistook this numbness for the cold and pulled up his tattered oilskin to keep out the sharp fingers of the wind. As he rowed out past the small rocky islands, he heard the sound of singing. Just Kittiwakes he thought. But no. It it wasn’t a sky sound. It started with a swell of blue and hushed away into sand.

The sound got in under his coat and tapped on his heart door. Just sea tricks he told himself. He rubbed his ears but the singing didn’t stop. Despite himself the fisherman rowed towards the little island. Following the sound that made him feel wanted and lonely at the same time.

There was movement. Pale flickers between the standing stones. Women. Moving so fast. So gracefully. Naked in the cold. A wild dance. Shadows on their skin like waves, like flames. He forgot his baited lines and scrambled ashore. He hid. Just to watch. The feeling rushing back to him – like cold hands held too close to the fire. Their dance slowed as the winter sun rose. The women put on their sealskin coats and – the fisherman could not believe it – they pulled up their hoods and their eyes grew dark and huge, their noses black and shiny and the seals slid back into the sea. Not women at all. The fisherman had heard such tales of seal women, from old sea dogs, dripping with whiskey and tears but he’d never believed.

The fisherman returned the next night and saw the seals wriggle off their skins: heads, hips and legs rising, then the women hid their sealskin coats. He watched the dancing. He heard the singing. His loneliness thawing. His head planning. The following night he picked up one of the coats, a deep grey pelt. It was soft and warm and smelled of beach smoke.

He held its warmth against his belly and waited. The seals slipped away into the water one by one except for her. He watched as she searched for her coat. Overturning stones and driftwood. Calling out to her skin in her seal tongue. The pelt thrumming in his hands, he stepped out from his hiding place, he did not know what to say – he just wanted to hear the singing, always, so he said ‘be my wife’, the coat held tight in his hands. She said she could not be wife as she came from beneath. He gripped her pelt closer. He told her that he had watched her dance, chosen her, would love her and only her, for her singing, for her strangeness and promised that after 7 summers he would return her skin and she could go free. She had no choice but to agree.

She lived with him as wife in his house. She dressed in rough wool and the cold skins of animals that smelled like bad deaths. She cooked and cleaned and brushed sand out of the house. And every time she sang he said it didn’t sound the same. He said why can’t you be quiet? Why do you look at the sea like that? Why do you wear that? Why do you eat that way? Why are you so strange?

In time they had a child. And she secretly taught her son the songs and stars from her world.

As time went on she stayed quiet and copied the other wives, her skin dried out and cracked: her eyes dulled, her eyesight grew dim and her hair fell out.

She asked her husband to return her skin now the eighth summer approached. But he said ‘you will leave me’ so he refused and broke his promise.

There was crying. There was shouting. There was breaking. The boy heard it all though they thought he was sleeping.

The boy closed his eyes and tried listen to the sound of the sea, the shush of the waves through stone, but deep inside that sound, he heard his own name being called. He left his bed and went to the shore and saw a huge shaggy silver seal. It scared him, he stumbled back, over a rock to get away from the water’s edge. Only it wasn’t a rock. It was soft. He smelled his mother on it – beach smoke and story breath – it was her skin and he ran home with it for her.

She held it close. It still felt warm. She felt her eyesight clear. Her breath came easier. Her short hairs stood on end. She rushed to put it on but saw her boy’s tears at the thought of losing her to the sea. She took his face in her hands and breathed her breath into his lungs.

And together they padded over the rocks to the water’s edge, then deep, deeper under the waves to her world.

Here amongst her people her colour returned. Her skin glistened. Her eyes grew sharp. But as she grew stronger her son weakened, being half human he could not stay.

She swam with him all the way to the shore. And cried at saying goodbye.

The boy became a singer and storyteller as he had survived being carried away by seal spirits. His stories came from two worlds and mesmerised. His songs and drumming came from two worlds and healed. He could often be seen talking to a seal with human eyes that many hunters tried to catch but never succeeded.

In some versions the Selkie takes her child under with her, sometimes she leaves her child in the human world, but always she leaves the fisherman to return beneath the waves.

Background to Selkie Myth

The Selkie myth is part of a wider family of therianthropic tales of animals or spirits who take on human forms. These seal women stories are cousins of Ondines, the water nymphs found in forest pools and waterfalls and Hulder, the Scandanvian randy forest spirits with tails, whose name means ‘covered / secret.’

It’s significant that the heroines of these stories are creatures that inhabit wild places but can take on human form and so they speak to that false boundary between animal and human, civilisation and wilderness that is key to deciphering the power of this story.

This tale is about a creature that comes from and is subject to a world beyond the laws of god and men. And so the Selkie makes a fiction of the world made for and by men and the rules women are expected to follow, especially rules that damage them. In Classic Tales of Animal Brides and Grooms, Maria Tatar explains:

‘Tales about swan maidens, Selkie, seals and mermaids can be found in virtually every corner of the world because in most cultures Woman was a symbolic outsider, was the other, and marriage demanded an intimate involvement in a world never quite her own.

That’s the thing about this tale – it gets it. That the civilised world doesn’t feel like it has been made for women. And this world is still being designed largely for men as Caroline Criado Perez’s brilliant book Invisible Women shows us that ‘everything from speech-recognition software to bulletproof vests, are designed for men as a default.’

These stories don’t have or want a single author they want to change, be told and retold because they are working out an issue as yet unresolved. They call to writers to find new meanings in them. Joanne Harris’s most recent adaptation the Blue Salt Road turns the traditional Selkie myth on its head by having a seal man as the captured hero. And this is significant because stories of theft and capture are about power relationships. Many artists have taken on the Selkie and its sister myths, and brought new meanings to them: Guillermo del Toro in the Shape of Water , Amy Sackville in Orkney , Louise O’Neill in The Surface Breaks .

These tales are not archaic leftovers, they are root stories, with their themes entangled deeply into the power problems humans play out again and again throughout history. And there is so much to be gained by weaving them into our own stories, by joining our roots to theirs.

The Selkie Myth, How Saints Die and Lessons About Madness

It is because of this rootiness that I return again and again to myth, folklore and fairytale to tell a story. By going under the surface of these stories we find new truths. That is why I write magical realism, where two worlds rub up against one another, disrupting and changing one another. It took me a long time to accept that I was a magical real writer, though it wasn’t news to those who knew me well.

I thought that if I was going to tell my first story, that of a child watching her mother’s mental breakdown, seeing the community turn against her, being labelled as damaged by school and social services – that this was the territory of social realism. I tried that. It hurt, it felt broken and it was a lie.

Because it was not the real experience of how mental breakdown affects a family. The cold light of realism showed only the breaks, the victimhood, the judgement. I had to go under, where the light can’t reach to show how the broken can survive and come home.

The only other stories that offered this transformational power were the stories I loved but felt somehow were childish – fairytales, folklore, myths, magical realism, domestic fabulism – call them what you will – there’s always something in them my toddler would call ‘sparkle magic’. I learned that magical realism is not the genre of escape but of revolution because change starts by questioning the limits of our accepted reality. When we stay in the real world we just get too bogged down in the limited rules, so that if there is a trauma, we can’t fix it there.

We need to jump into a darker place, where the imagination can get to work on it. In psychology this is known as a paracosm, an imagined world where trauma can be resolved.

To find the truth in my story I had to ‘tell it slant’, to embrace all myth and magic had to offer – to go as I like to call it as I’m from Yorkshire – The Full Bronte. So I created an imagined world where wolves of the sea could turn up at the school gates. That story is How Saints Die.

SLIDE 4: HOW SAINTS DIE

Meet my book HOW SAINTS DIE

Let’s start by looking at the parallels between How Saints Die and the Selkie Myth

How Saints Die is about a fisherman, who marries Kate, a strange and beautiful woman from across the water (technically Ireland). They have a child together, Ellie, who is strange like her mum and practical like her dad. But far from home, Kate begins to diminish, to break and desperately wants to find a way home, back to her people believing that this will fix her. And she needs her child’s help to get there. The roots of the Selkie myth are loosely there.

But my story got stuck, because staying with reality wouldn’t allow me to explore the where Ellie got her resilience from, the relationship between Ellie and her mother Kate, or what Kate needed to survive.

Learning about the Selkie story, spending time with it, trying to understand the role of the animal and the sea showed me new directions that I needed to take for my story to feel true, and they were very magical and very real.

SLIDE 6: WOLF ELLIE THREE IMAGES

Meet my wolf friend.

These were the images I kept on my notice board whilst writing How Saints Die

They all mush up the boundary between animal and girl, captured and wild.

In the Selkie myth, the seal plays the part of a woman in the real world, but is truly wild and comes from beneath. Because of this I knew I needed a way to express the deeper wild nature of Ellie, my ten year old protagonist. The power of fairytales is that they take us to where the light cannot reach, this is the journey of the story and the journey of the emerging self. In myths concerning animal transformation, like the Selkie – we encounter the animal aspect as a shadow-self, the part we do not show in the light of being good and normal and civilised. In Jungian psychology the shadow aspect is an unconscious part of the personality which the conscious ego does not identify in itself. It’s the ‘Me, no, I’d never do that’ part. But there is something really dangerous about not being aware of our shadow self. Not only is it the bits of our personality we don’t want to own up to. It is the place where positive and powerful aspects may remain hidden

. So, in a culture that represses us, we exile our need to speak, who we truly are or might be to the shadow. If we are going to be true to ourselves then we need to bring the creature out of the shadows into the real world and challenge the power of that reality.

In the Selkie myth, the true self is the seal, the disguise is being a woman, because there is no place for the wild self to walk free in the domesticated world. She disguises herself as civilised.

Ellie, I knew was also a wild thing at heart, playing the part of ‘Ellie who says yes’ at school when she was truly ‘Ellie out of bounds’. I had to give her a shadow self, not just to express her strangeness but to protect her from an adult world that was failing her.

I began to research wolves and the more I learned about them, the more I realised Ellie’s shadow was a wolf. They are fiercely loyal to their own family, they play tricks, they nose out traps, they are spirit animals who can pass between worlds. And Ellie needed this power the most – so that she could reach her mother in the underworld. So I created a chance for Ellie to summon the wolf from under into her world. In the Selkie myth, an unhappy woman can summon a seal lover by crying seven tears into the sea. When Ellie is first taken to see her mother in a mental institution her mother asks her to perform a ritual to summon her dead granny. Ellie must carry out the Irish ritual of lighting the Halloween light to guide the dead and gone home for one night.

Read Pg 69 How Saints Die from MUM, MUMMY

But like all good fairytale tasks, it goes bad –

Read pg 77 from There is a shudder

Instead of her Granny, a wolf breaks into Ellie’s world from the sea. This sets in motion the tension between the obedient and the wild, untamed free child. Ellie knows holy, she knows that saints suffer and die but they can’t explain how to suffer and survive.

Ellie’s folk-religious rite doesn’t deliver another adult, not even a dead one or a saint. Instead she summons a wolf, with claws and teeth and it is better able to protect her from all she fears, including her mother. The wolf runs wild in the human imagination because it has the power to save or devour, and Ellie’s wolf remains true to that uncertainty.

I wanted the wolf to be ambiguous – to not be a force for good or bad. Because it comes from a place beyond our morality. It comes from under, where the laws of god and man don’t apply.

Going Under In How Saints Die and What it Tells Us About Breakdown

Next, I want to share with you what the Selkie myth can tell us about breakdown and mental illness. I was determined when writing How Saints Die to avoid the handwringing stereotypes of madness that infuriated me. That’s not what breaking looks like.

In the Selkie myth we glimpse what it is for someone to break. The Selkie woman loses her eyesight, her hair falls out, her skin dries out. We know that this breaking down of her body is because she cannot survive in the wrong element. She belongs to water.

That is exactly what I saw watching the slow breaking of my mother. It wasn’t because she was made wrong. It was because she belonged to the under-world, not Redcar in the 1980s. The Selkie is very much a tale of the stranger in a strange land, of the immigrant other expected to assimilate.

My mother was the Irish enemy at the height of the Troubles in the 80s. Even in Ireland she did not fit. There was no future in Ireland. Her dad did not want to educate the girls. She came to England. She worked her way up from being a waitress to being head chef. She bought her own house when she was just 23. But by the time she had faced the trauma that caused her breakdown she had become the mad-paddy next door.

Read QUOTE PG 64 -65 – ELLIE FIRST SEES HER Mum

Madness is a response to the constraints of the society we try force ourselves to fit into. Mary Wollstonecraft tells us in Maria: “The misery and oppression, peculiar to women, arises out of the partial laws and customs of society”. The Selkie myth, is about wild creatures masquerading as humans, and because they don’t belong they need to return beneath – or as my dad explained, to the place where the laws of man have no power.

The return under, may look like a mental breakdown but it is part of the process of healing, Jeanette Winterson tells us in her incredible memoir, Why Be Happy if You Could Be Normal: ‘Going mad is a process. It is not supposed to be the end result.’

The Spirit Child

In the Selkie story, it is the Selkie’s child who returns her coat, who enables her to transform and gain access back to her world under the sea. The Selkie needs a child, who belongs to both the human and wild world to help her get to the sea.

But in my story, Ellie’s task was not to let her mother go and stay under, but to bring her back. It is not the story of loss but of survival.

In the practical myths of sea lore there is a practice called Salvage. If you are a fisherman who is willing to go and support a lifeboat rescue, risking your own life, then you get salvage rights to the wreck and what the sea leaves behind.

SLIDE 6: SALVAGE QUOTE

Here is Ellie asking her dad what exactly salvage means

Read ‘It’s a sea promise, it means you have to bargain something to get something back.

What like?

Something precious, something you love, mebbe even your life chick. The sea won’t take less.

In order to bring back her mother, Ellie must make a sacrifice, it involves giving up her innocence in exchange for her mother – but I won’t give away the whole story.

The salvaged thing returns changed, the sea has transformed it, broken it and remade it.

Read pg 201 from THE BIG BRASS CLOCK

The sea takes the broken thing and returns it. No longer broken, no longer perfect – but something that has been under and survived.

There is a darker reading to the Selkie tale than the story of going under and surviving and it is this that I am journeying into for my next story The Bait Boy. A story about coercive control. How it works and how to survive it.

SLIDE: 7 THE SELKIE AND COERCIVE CONTROL

4.30 check

As I said at the beginning of this talk, the Selkie is a danger story. On the surface, it is almost a romance – a lonely fisherman and a beautiful seal woman. And there are related tales like Agneta and the Sea King, that are about falling into an out of this world love, but even Agneta is brought back to reality by the Church bells. The Selkie tale contains deep coded messages about how we can be tricked into love, why we stay in a captured state and the damage this causes.

We see a free creature, cut off from her people, coerced into marriage and that she suffers until she is free.

The law only recently acknowledged that this controlling behaviour is criminal in December 2015. The law defines coercive control as a “continuing act, or pattern of acts, of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim”.

But what constitutes a threat, how do acts of humiliation cross from ‘just kidding’ into damaging, what if intimidation disguises itself as protection? How do we know it is harm if we have adapted to it? How do we know it is punishment if we are told we deserve it? What if it’s too exhausting to be afraid all of the time so that we just become numb?

Perhaps the difficulty of these questions explains why despite the increase in cases of Coercive Control being reported, few are successfully prosecuted.

In a report by Charlotte Barlow, Lecturer in Criminology at Lancaster University, she highlights that police have missed patterns – ‘evidence of repeat victimisation, a pattern of abusive behaviour’ leading to fewer charges being made. There are opportunities being missed to identify repeated patterns of abusive behaviour that could lead to prosecution.

Let’s just hear that again. There are opportunities being missed to identify repeated patterns of abusive behaviour that could lead to prosecution. The key word here is pattern, the law focuses on the consequences of the process but it is the pattern that we, the police, support workers and the criminal justice system need to be made aware of. There is a pattern to abuse that can be traced.

Tracking and understanding these patterns allows incredible organisations like The Freedom Programme to turn people’s lives around. The Freedom Programme is a course for victims of domestic violence and it examines the roles played by attitudes and beliefs on the actions of abusive men and the responses of victims and survivors. The aim is to help them to make sense of and understand what has happened to them, instead of the whole experience just feeling like a horrible mess.

These patterns have been identified by criminal behaviourists, survivors and by the unknown storytellers who gave us the Selkie myth. The Selkie myth tracks how the control is seeded, how the victim has no choice and cannot see their trap.

And it goes beyond the vague definitions of threat, humiliation, intimidation and other abuse to show what the lived experience of coercion looks like and how to survive it.

I first read the story of the Selkie in Clarissa Pinkola Estes life changing book – For Women Who Run With Wolves when I was 23. I was a stranger in a strange land. A working class girl at St Andrews Uni. A friend recommended the book after I’d talked a little about why I’d just got a huge protective tattoo drilled into my back. Why I thought I was to blame when my first boyfriend put his hands around my neck and squeezed. As I read I wished I’d read it at 16 years old, maybe 14. I wish I’d know that a trap can look so much like love.

Let’s go deep into the story and look at the lessons it shows us.

There are three key elements of the story I’d like to focus on to show how the Selkie myth helps us to understand the journey into and out of coercive control.

- The theft from and capture of the innocent.

- The symbolism of the animal skin.

- Going under.

- The theft from and capture of the innocent.

In the Selkie tale the woman is tricked into a relationship and she stays there because she has no choice. Her coat, her means of escape has been stolen.

One of the greatest myths about coercive control is the belief that the victim can ‘see it coming and get out’. The victim is blamed because they cannot free themselves. (I’ll use the word innocent, rather than victim from now on, as the journey of story is always from innocence to knowledge gained through suffering and the gaining of knowledge doesn’t make us victims it makes us wise).

What the Selkie tale clearly demonstrates is that the innocent has no choice but to agree to the relationship. The fisherman steals her seal skin coat – her means of return back to her own world. She is tricked into giving up her freedom and is then powerless to bargain her way out of this situation. Remember she is naked during this theft, vulnerable, this is the first act of intimidation and humiliation but she doesn’t know it yet. She is trapped in his world and must do as he says to escape because he can hold the threat of the destruction / of not returning her coat over her. In the Selkie story the innocent is not culpable. It is the fisherman’s act of theft and its consequences that is flagged as dangerous. He is not portrayed as a predator, the big bad stranger. He is portrayed as a lonely man – and so his need and desperation make him suspect and drive him to humiliate, intimidate and threaten his way into a relationship.

The first consequence of the theft of the seal skin coat is that the Selkie cannot go back to the sea, she therefore can’t communicate with her people.

Criminal Behaviourist Analyst, Laura Richards, identifies isolation as part of the pattern of coercive control. The controller cuts the innocent off from friends and family, so that they have no one to help them and this also stops friends and family from seeing the extent of the abuse.

The Selkie cannot return home, she becomes a stranger in the fisherman’s land, entirely dependent upon him. Just as in coercive controlling relationships.

Richards identifies pressuring and guilt tripping as the next part of the abusive pattern.

The fisherman steals the Selkie’s sealskin coat and promises to return it only if she remains in his world as his wife. This is a threat disguised as a bargain. The Selkie does not want to, she says she is ‘from beneath’ that she cannot be wife, but using the coat as a bargaining tool the fisherman pressures her into the relationship. He uses his loneliness to keep her. The tale shows that there is no clear predatory act that would warn the innocent to get out but a subtle play of pressure and manipulation into a relationship that at first feels real because of the power of someone else’s need.

Fairytales and myths like the Selkie story not only reveal the danger of patient predators but of the predatory expectations of our culture. This world requires that women make deep personal sacrifices to be wife and mother, sacrifices to career, education, aspirations and physical and emotional well being. So, the initial stages of the coercion pattern that requires a woman to give up what is precious to her, feel exactly like the brand of love women have been sold and the brand of womanhood they should perform:

She was intensely sympathetic. She was immensely charming. She was utterly unselfish. She excelled in the difficult arts of family life. She sacrificed herself daily. If there was chicken, she took the leg; if there was a draught she sat in it — in short she was so constituted that she never had a mind or a wish of her own, but preferred to sympathize always with the minds and wishes of others. Above all — I need not say it —-she was pure. Her purity was supposed to be her chief beauty — her blushes, her great grace. Woolf Professions For Women

The tale is a warning against too much self-sacrifice and the temptation to care for, nourish and fix others. The story challenges the idea that sacrifice is an aspect of femininity with a truth about the human need for self-actualisation – the Selkie has a deeper purpose beyond and beneath being wife. For a time, the Selkie forgets that she is other, but slowly she learns that she is not solely responsible for the fisherman, his home or their child and commits the act that is most taboo in our society for women – she leaves her family, not because she is selfish, but because her survival depends upon it.

In the powerful poem of resistance The Journey, Mary Oliver explains this wake up moment:

“Mend my life!”

each voice cried.

But

as you strode deeper and deeper

into the world,

determined to do

the only thing you could do —

determined to save

the only life that you could save.”

As the pattern of control deepens, punishment comes into play. Richards tells us that rules and regulations are imposed by the controller and the innocent is punished if they don’t comply. Punishment can take many forms of negative behaviours that are damaging, like public humiliation or ignoring and do not necessarily have to be violent.

In the fisherman’s world, the Selkie must play the part and follow the rules of being a good wife, taking care of her husband and giving him a child. In the experience of coercive control, the innocent must strictly adhere to the rules and regulations set out by the controller. The rules are endless and senseless, they are impossible hoops the innocent must jump through. They can include what the innocent must wear, where they go, who they see. The goal is to curb behaviour. The innocent must follow the rules to prove her love, but the controller is above these rules. The Selkie follows her part of the bargain, she remains with him for seven summers but when the eighth summer arrives and she asks for her freedom the fisherman denies it, saying that he is afraid she will leave him and so the fake marriage is exposed as a prison. This part of the tale shows us that obedience only leads to further entrapment, that the controller cannot be bargained with, the punishments will still come and freedom cannot be achieved through cooperation.

Because the nature of coercive control is so subtle and involves a slow process of the erosion of rights and freedoms rather than outward physical violence it is hard for the innocent to identify the signs from within the relationship but the tale clearly shows us that physical symptoms are a sign of abuse:

- The loss of weight, the drying out of skin, the loss of sight, losing hair.

Whilst the mind adapts and normalises the abnormal, the body remembers and shows the trauma. In the groundbreaking book The Body Keeps Score, psychiatrist Bessel Van der Kolk tells us:

“Traumatized people chronically feel unsafe inside their bodies: Their bodies are constantly bombarded by visceral warning signs, and, in an attempt to control these processes, they often become expert at ignoring their gut feelings and in numbing awareness of what is played out inside. They learn to hide from their selves.” (p.97)”

― Bessel A. van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma

So the Selkie’s body is shouting loud and clear that something is desperately wrong. But she cannot listen to it. The only way to survive in these circumstances is to numb to reality and ignore instincts. This is one of the reasons the innocent can’t just walk away they have deactivated their instincts in order to survive.

The story warns us to watch for and listen to the signs of the body to reconnect to our body-sense when it tells us to run. But for the Selkie woman – this part of her self-protection has been stolen, she is skinless and she has to ‘come back to her senses’ in order to awaken to a way out.

SLIDE: 8 THE ANIMAL SKIN

- The Symbolism of the Animal Skin

The symbolism of the animal skin is perhaps the most important message of this tale. In the story the Selkie’s skin is stolen – but what does that mean?

What is the power of an animal skin?

Animal skins have never simply been clothes. They have been used as part of human rituals to travel to other worlds, to imbue the wearer with the power of the spirit animal and as medicine bags.

Shamans wear animal skins and feathers to see the truth and to travel to other worlds.

There are many examples of homeopathic imitation of animals in medicine. ‘An Hidatsa woman experiencing a difficult birth might call on the familial power of the wolf by rubbing her belly with a wolf skin cap’ Of Wolves and Men, Barry Lopez

From Rabbit’s feet to Judges Ermines, animal skins confer power and good fortune on those who wear them.

SLIDE: 9 The Hairy Woman Sapsorrow

Skin is not just skin, it is covered in hair that senses, feels, protects. Hair is in constant communication with the exterior world sending messages through the body to the brain – cold, hot, happy, danger. We say ‘my hackles are up’. The hackles are the erectile hair on the back of an animal’s neck. They are raised as a warning, it is a defensive act. To have your furry skin stolen means that your ability to sense danger, to protect yourself, to warn others has been stolen.

We’re talking about the language of hair and the power of the Hairy Woman in fairytale, society and literature. The Hairy woman is seen as powerful and repulsive at the same time, but she is also uncanny, unnatural and a threat.

In fairy tales the hairy woman takes on many forms – all of them subvert or disrupt her social destiny as wife / mother.

Slide: 10 The Crone

There is the crone, Baba Yaga or wise woman with whiskers on her chin. Her hairiness symbolises her age and wisdom. This figure has been diluted to the big bad witch but as the Baba Yaga she is a healer and a teacher. She oversees the life/ death / life cycle of the natural world. She is the mythic monstrous mother who consumes children – Medea and Lady Macbeth. She also teaches fools how to be wise. In Diana Wynne Jone’s Howell’s Moving Castle – the heroine Sophie is cursed to become an old woman, but only in this form can she stop being the good and obedient fool and find her true self. Above all the crone is the keeper of stories. Woolf tells us ‘We think back through our mothers’, so when the coat is stolen – the Selkie is cut off from the collective, unrecorded history of women and their stories that would help her in this task.

The crone is one of the triple goddesses – the maiden, the mother and the crone. The Crone is the third act of womanhood, she knows what happens after ever after. Fairytale has always been the keeper of the Crone’s story, but in contemporary stories we are obsessed with the naïve beauty. We are only just learning that there is a place for Crone stories on bookshelves and on screens. A place for the stories of women who faced the big bad and survived. Writers who do this really well are Viv Albertine, Rachel Joyce and Elizabeth Strout. Now more than ever I need to hear the crone speak about living, trying, failing and surviving as a woman rooted in her own power. The more stories of women who have reached their third act, who have tried and failed at life and just get on with it – the better.

Whereas the invisibility of older women is a problem, that same invisibility is can be a power for the Hairy Woman. The second form of the hairy woman in fairytale is the Animal Disguise: in this tale type the young girl must escape an unwanted marriage, most often to her father. When the innocent is forced to go against nature she finds refuge and escape through an animal form. This occurs in tales like The Donkeyskin Princess or Sapsorrow. In these stories the princess is tricked into agreeing to marry her king-father. She delays by setting a condition upon the marriage – demanding three impossible dresses of gold / silver / starlight. Buying time in this way allows the princess to make an animal skin disguise and on the night before her unnatural wedding she makes her escape unseen as an animal fleeing the castle.

In Anthony Minghella’s retelling of Sapsorrow for Jim Henson’s The Story Teller, the princess enlists the help of the animals she has befriended to cover every inch of her in their fur and feathers. When the king arrives to claim his bride she cannot be found:

Only a strange creature of fur and feathers scurrying along the ledges, disappearing into the bushes, swimming across the moat. One guard noticed and thought he’d seen a large cat, another described a dog, a third a seal.

The Hairy Woman in this tale becomes an unseen part of the animal kingdom, disguising her sexual availability under a fur coat. The skin offers her the power of invisibility to move freely in a world where before she was property to be guarded or potential prey.

This animal invisibility that allows access to all territories of day and night is still denied to women. Woman are told that to keep safe we must walk only in the light, be sensible, be safe or they put themselves at risk.

Nottinghamshire police recently said this in a Facebook post “Taking a risk when it comes to walking alone at night is not one of those things we should be doing. Women who walk alone especially at night are at risk of harassment, or even physical assault.” The post was swiftly deleted but nevertheless, the advice reveals the ways in which fear is used to limit women’s territory.

I used to work in a dodgy seaside nightclub. I was told to get a taxi home. One driver wanted to take me out onto the moors to show off his new car. Another tried to take pictures of me without my consent. Another asked me if it was abuse if the person wanted it. I started walking home. I was accompanied home by street cats.

The hairy woman moving freely under the cover of darkness is one thing. But the hairy woman at large on the pages of beauty magazines is another.

SLIDE: 11 Sophia

Meet model Sophia Hadjipanteli and her eyebrow Veronika. She has the classic bone structure and beauty that we expect of a traditional fashion model – but she will not go skinless and remove her brow.

The 22-year-old’s natural look has made her an internet sensation – with almost 300,000 followers on Instagram she is the self-styled leader of the “unibrow movement”.

But so alarming is her hairy-beauty and her refusal to cut her fur away that she has received internet death threats. This says much about the power of hair.

The average woman in the UK spends £23,000 over the course of her lifetime on hair removal. Almost the cost of an undergraduate degree. But we have to ask what is it that scares women about this kind of power?

Classic and contemporary fairytales still feature the hairless woman as the heroine. But writers like Angela Carter, saw the shadow tales underneath the cleaned up and moralising fairytales that are told to children. In her collection of short stories The Bloody Chamber she restores the connection between hair, beauty, sexuality and identity to show that women are ‘hairy on the inside’, not merely a pubic allusion, but that the animal self is in tact. In the retelling of Beauty and the Beast – The Tiger’s Bride, Beauty discovers that the tiger is suffering because he is a tiger in man’s clothing. She is not frightened instead She says to herself “a tiger will not lay down with lamb but the lamb could learn to run with tigers.” In response the tiger kicks off her bare human skin to reveal a tiger beneath. This is a story of love between two honest animals who are not engaged in the performance of being male / female.

The selkie myth highlights that the problem of the hairless woman is the mind / body problem and women are still paying the price.

In the Christian framework, Eve was made from Adam’s rib and therefore must be subject to his reason (which she was not given). Milton tells us in Paradise lost when Eve pledges her subservience to Adam:

O thou for whom, And from whom, I was form’d; flesh of thy flesh; And without whom am to no end; my guide And head, what thou hast said is just and right. (IV, 440–443)

As Eve is the headless passion that succumbs to appetite and temptation she bears the brunt of divine punishment – to have pains in childbirth and bleed. She is from this moment suspect and subject to control.

This binary framework that divides male / female; reason / passion; human / animal; divine / cursed impacts women’s freedom, identity and status.

The implications of this for coercive control, for successful prosecutions in the current criminal justice system where just 29% of court judges are women, is that the female body is still seen as dangerous, and suspect – and therefore in need of taming and ultimately control.

There are so many ways the sealskin cost can be stolen in a society that sees women in this way but consequences of its loss are costly.

‘Psychologically to be without pelt causes a woman to pursue what she thinks she should do rather than what she wishes.’ Clarissa Pinkola Estes

When I was writing my book How Saints Die I wanted to capture what it was like to know a woman who was damaged and numb and who needed to return home in the character of Kate:

“And you drink your tea and pull on your cigarette and your throat burns and out of the blue smoke it comes again. Dead. Swallowing up the whole kitchen. And you’re too hot, but it’s raining outside so you get up to open the window to get to the rain and you forget the knack and you break it. And your head is splitting and you wish the world would open up and swallow you. And it does.”

How Saints Die

The Selkie, in possession of her sealskin coat represents the whole, wise woman, the untamed and undomesticated self that is free. Being separated from her skin means that she is living a fake life, the tamed life:

Not as she is but as she fills his dreams

- unless she finds a way to get it back.

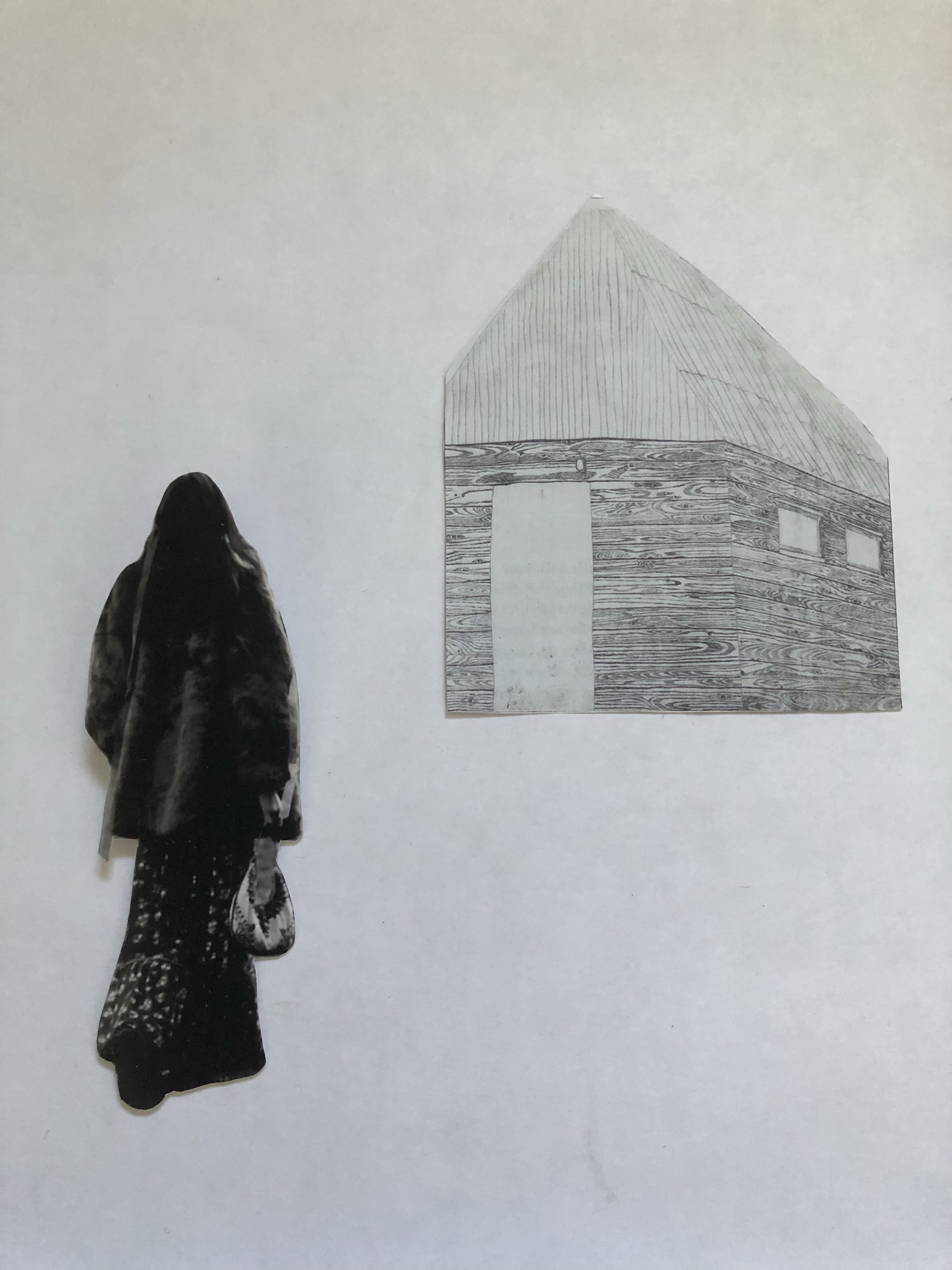

SLIDE 12 THE SEA CALLS US HOME

- Going Under – The Sea Calls Us Home

The question most people ask about coercive control is ‘Why did you stay?’, when by far the most relevant question is ‘What finally made you leave?’. So far we have seen that obedience will not get back the skin. There is a point in an intolerable situation that provokes the awakening of our true self, the suppressed self that rises up from the depths of the ocean and says enough is enough ‘come home’. And we have to follow that voice.

In the story it is the Selkie’s child who hears the call from the ocean and retrieves the skin that enables the Selkie to return home. What is this voice and where does it come from?

“It is said that disembodied voice dreams may occur at any time but particularly when the soul is in distress; then the deep self cuts to the chase. A woman’s soul speaks and tells her what must come next” Clarissa Pinkola Estes.

I wonder if it is because when we were children, though we were innocent our instincts were still intact and hadn’t been civilised out of us that it is the child who hears the voice. The reason why the innocent chooses to get out is different for everyone, sometimes it’s to protect their children, or something reconnects them with their old-young self – an old friend. Whatever the spark there is no going back. The Selkie only had to hold her coat to get her eyesight back. All that’s needed is that brief connection and the illusion falls away . With the skin back the woman can see clearly, get out and part of that journey means going under. Home is not necessarily the place where we grew up. It is an internal place where we can nurture and heal ourselves. It is Under. In her poem Diving the Wreck Adrienne Rich writes:

There is a ladder

The ladder is always there

Hanging innocently

Close to the side of the schooner

I go down

I came to explore the wreck

I came to see the damage that was done and the treasures that prevail.

This rite of going under takes us back to the practice of salvage, taking what is broken and making it into something else. This is what’s required in order to escape from coercive control and survive. Going under takes courage to leave what is known and submerge into the darkness. It takes courage to look at the damage done to us. And it takes even more courage to look past the damage to find the treasures that we’ve won on the journey from innocence to experience. It is only by going under can we fully realise the transformation – the sea change acting upon us, changing damage into wisdom.

‘Those are pearls that were his eyes

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea change.’

Shakespeare’s notion of sea change speaks to resilient, unruined heart that never fades but can transform. What makes this transformation possible is the retrieval of the seal skin. It is the true self not the act. The Selkie is not a trapped or cursed princess who must or wants to give up her hairiness to marry the prince. The Selkie is animal deep down – wild, undomesticated, from beneath and not subject to a culture that demands goodness and obedience from the suspect female. This skin enables the woman to cross over that edge from the human world into the sea where the laws of man end.

Slide 13: Contacts

Conclusions

The Selkie myth predates the Christian edict to control women as suspect and carnal brings. It predates the notion that the animal is the opposite of the divine, the body the enemy of the mind – the Selkie myth restores the sacredness of the body as a force of instinct and knowing. It tells us that to be safe we do not need to seek a protector from ourselves but to trust the hair on our backs when it raises.

The Selkie story shows us what happens when we make ourselves skinless and don’t trust our instincts. But it does not judge us or victim blame us. It shows us how to find and keep our skins for next time. It shows us that to be wise:

You do not have to be good

You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.

Mary Oliver

Slide References

Slide Thanks

Carmen x

Cixous, Helene, The Laugh of the Medusa, The University of Chicago Press

Hemingway, Ernest, The Old Man and the Sea

Tatar, Maria, Classic Tales of Animal Brides and Grooms

Criado Perez, Caroline, Invisible Women, Chatto and Windus

Harris, Joanne, The Blue Salt Road

Del Torro, Guillermo, The Shape of Water

Sackville, Amy, Orkney, Faber and Faber

O’Neill, Louise, The Surface Breaks, Scholastic

Winterson, Jeanette, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal

https://www.freedomprogramme.co.uk/

Woolf, Virginia, Professions for Women

Oliver, Mary, Wild Geese

Bessel A. van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma

Lopez, Barry, Of Wolves and Men

Carter, Angela, The Bloody Chamber

Milton, John Paradise Lost

Pinkola Estes, Clarissa, For Women Who Run With the Wolves

Riche, Adrienne, Diving the Wreck

Ah this is such a profound piece on selkie folklore. I’ve been drawn to this myth for several years, writing a story in fits and starts, struggling to comprehend just why I’m so gripped by it. Reading this has enriched my thoughts and also made me more aware of what the hairy me already knew. I will definitely be reading your novels.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much I hope you enjoyed How Saints Die x

LikeLike